New perspective on DNA variations leads to explanation for rare disease

Why am I becoming unwell? For a person suffering from a rare disease, the answer to that question is often a long time coming, or else it never comes at all. Occasionally, however, researchers do find the proverbial needle in the haystack. The team led by Prof. Eric Legius has found a new explanation for the condition known as Schwannomatosis, thanks to research financed by the ‘Fund for research into Schwannomatosis’, which is managed by the King Baudouin Foundation. This is good news not only for the families who are carriers of the condition, but also for research into genetic explanations for rare diseases in general.

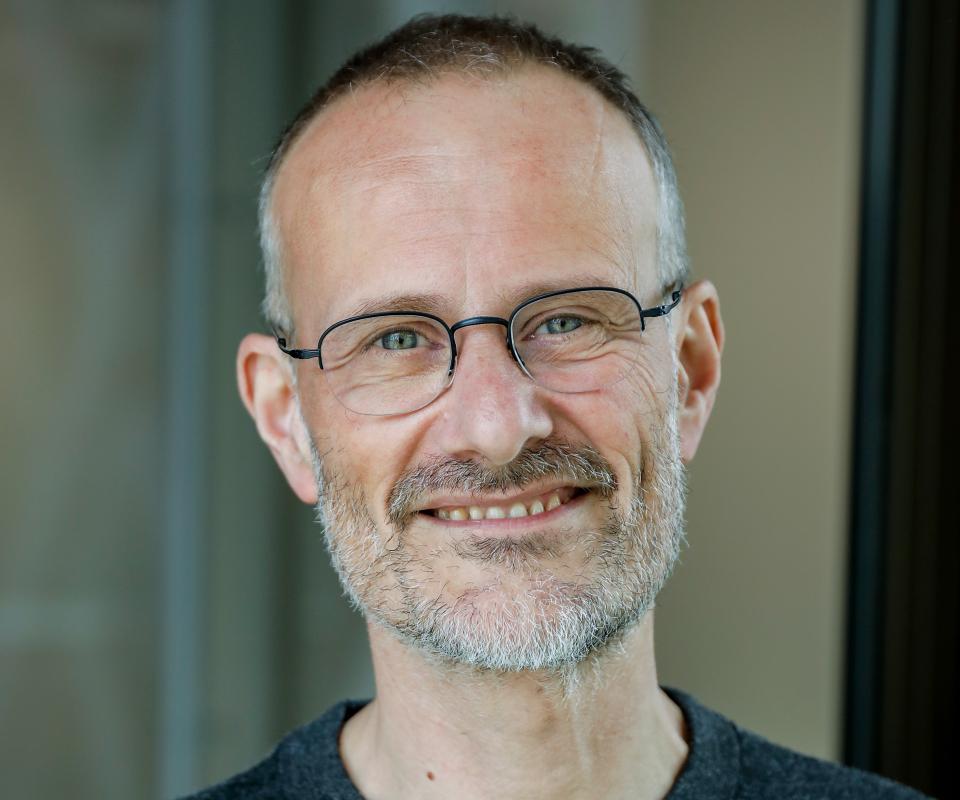

So for a researcher, when you find the genetic explanation for a rare disease, is it time to break out the champagne? “Well I did say a rude word!”, laughs Prof. Eric Legius, “because I had never noticed it before! We had overlooked it so many times!”

Geneticist Eric Legius is head of the Centre for Human Genetics at UZ Leuven and a specialist in the rare diseases neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis – there is even a variant of neurofibromatosis which is called ‘Legius syndrome’, “although the decision to call it that was not made by me!”. He speaks the language of genes, chromosomes and diseases as fluently as his own language, but fortunately he is also well versed in explaining the basics of genetics to people, including patients and their families, for whom the jargon sounds like pure gibberish.

Pancake around the nerves

Let’s start at the beginning: with the Schwann cells, named after their discoverer Theodore Schwann. Those cells are “like a rolled-up pancake”, forming a layer of insulation around nerves and the axons of nerve cells. In Schwannomatosis these cells grow in an abnormal way, causing tumours which are known as Schwannomas. It should be said that these are benign tumours: they stop growing after a time, do not metastasise and they do not invade surrounding tissues. Nevertheless, they are not always harmless, depending on where in the body they are located. For some patients they cause no symptoms, but others have severe nerve pain. “In that case you can try to peel off the Schwannoma by means of a surgical intervention. However, there is always a risk that the nerve will be damaged, resulting in sensory loss or even paralysis”, says Eric Legius.

Very occasionally a person with no genetic predisposition might develop a single Schwannoma, but if there is more than one in a person’s body, that is the signal that their Schwannomatosis may be due to a defect in the genetic material. “If one of your parents is a carrier, there is a one in two risk that you will inherit it directly, whether you are a boy or a girl.” It is estimated that one in 70,000 newborn babies will get Schwannomatosis during their lifetime - which means there are about 150 Belgians with the disease. “That is probably an underestimate, however”, says Eric Legius. “Here in our centre we are already following up about 50 of them.”

Search for the culprit

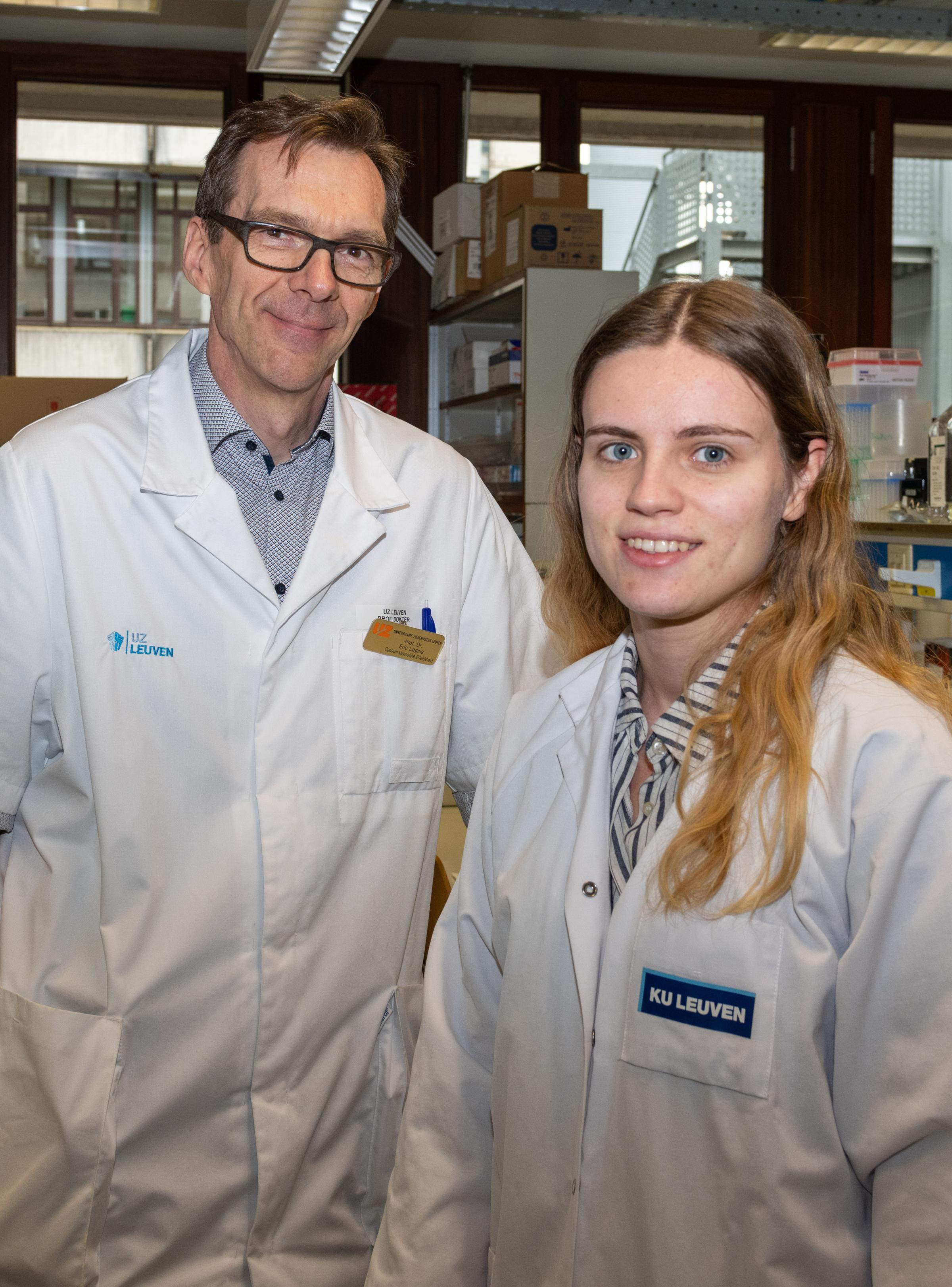

One of the families whose members were followed up in Leuven was a puzzle for the researchers - and in particular for Ph.D. student Lise Van Engeland, who worked on the analysis of their DNA. “We already knew that a defect on one gene on chromosome 22 – SMARCB1 – causes Schwannomatosis. In this family, however, that gene was normal. Working alongside the research laboratory of our Flemish colleague Ludwine Messiaen in the US (University of Alabama) we carried on searching. She had discovered that in some families the cause was a mutation in the LZTR1 gene, which is also on 22, right next to SMARCB1. But no, that one was completely normal in our family too...”

A gene is a piece of DNA code (a series of letters) which has to be ‘read’ to make proteins. That is done via an intermediate step involving RNA, which is a kind of copy of the DNA. “Could it be that the error was occurring during copying? But no, that turned out to be happening perfectly too.”

“We were already sure that the occurrence of Schwannomatosis was clearly linked to the inheritance of chromosome 22 in this family. When we carried out a genetic analysis of the whole of chromosome 22, there was nothing remarkable at first sight, but then we noticed something: just before SMARCB1 there was a variation that had never seen before. Was that the explanation?”

False start

It sounds exciting, but we are beginning to lose the thread... Never seen that variant before? “Your DNA consists of about 6 billion letters in a specific sequence, which is different for every person - that is what makes you unique. Only about 2% of it is the code for making proteins, which regulate the functions of all our cells. About half is made up of repetitions that do not code for proteins. As for the large number of remaining letters, we don't really know whether they do anything important or not.”

But here is one last piece to complete this crash course in genetics: a gene - which means a sequence of letters in a specific order, in sets of three - begins with a start codon and ends with a stop codon. These are combinations of letters that mean ‘the code starts here’ and ‘it stops here’. The variant that Prof. Legius’s team was looking at is before the start codon of SMARCB1, and it turns out to disturb the way the code is read, because it creates a ‘false start’.

This false start makes an unusable protein that does not function and gets broken down as soon as it is produced. “You always have two copies of chromosome 22, and the SMARCB1 gene on the second chromosome 22 can take over that role. Until the chromosome 22 with the functional copy of the SMARCB1 gene is lost by chance during a cell division in a Schwann cell, and then the Schwann cell will not make that protein at all any more. At that point things go wrong and a Schwannoma develops.”

A new place to look

Found it! This is wonderful news for some of the families involved in Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy. From now on, if they want to have a child and choose to do so, they can use in vitro fertilisation to test the embryo at the earliest stage and only have embryos implanted that do not carry the defect. It is also important to understand the cause correctly for the sake of a possible treatment in the future.

“We have shown that it is also worthwhile to look at the variants just before and just after genes.”

Is this useful for scientists in any other way? “It certainly is. We have shown that it is also worthwhile to look at the variants just before and just after genes. The importance of this goes further than those families: we are looking at a mechanism here that is not picked up by the known mutation analysis techniques which our computers are programmed to carry out. This new place to look has already been found to be useful in other research. We are not the only people who have used it, but we have strengthened the argument that you should be systematically looking at those variants too.”

The ‘Fund for research into Schwannomatosis’ was set up by an anonymous family and it has financed the research. The team led by Prof. Eric Legius at the Centre for Human Genetics of UZ Leuven has benefited from the cooperation of many members of the family who provided their genetic material for analysis. The team led by Prof. Laura Papi at the University of Florence in Italy also contributed to the research by commissioning the analysis of genetic material from a number of families followed up by the team who had shown exactly the same genetic variant.

Other stories

Inspiring engagement!

Pancreatic cancer: gradually untangling a complex knot

Health Research

“In families where there are more cases of pancreatic cancer, we are also seeing an association with colon and breast cancer.”

From asthma research to better treatment for cystic fibrosis complications?

Health Research

"When we see a patient whose cystic fibrosis is deteriorating, it is often hard to identify the cause. There is a need for better diagnosis of allergic reactions to fungi."

Other calls

Fund Abefradoc-Benevermedex - Assure your future

Support to research in the field of private insurances for the benefit of victims of accidents

Ongoing

Fundamental research on the mechanisms of pediatric cancers

Call for fundamental research on the mechanisms of pediatric cancers with clinical translation

OngoingOther publications

Other philantrophy

Other press releases