Revisiting Congo’s history to build its future

“Our citizens have always refused to surrender.”

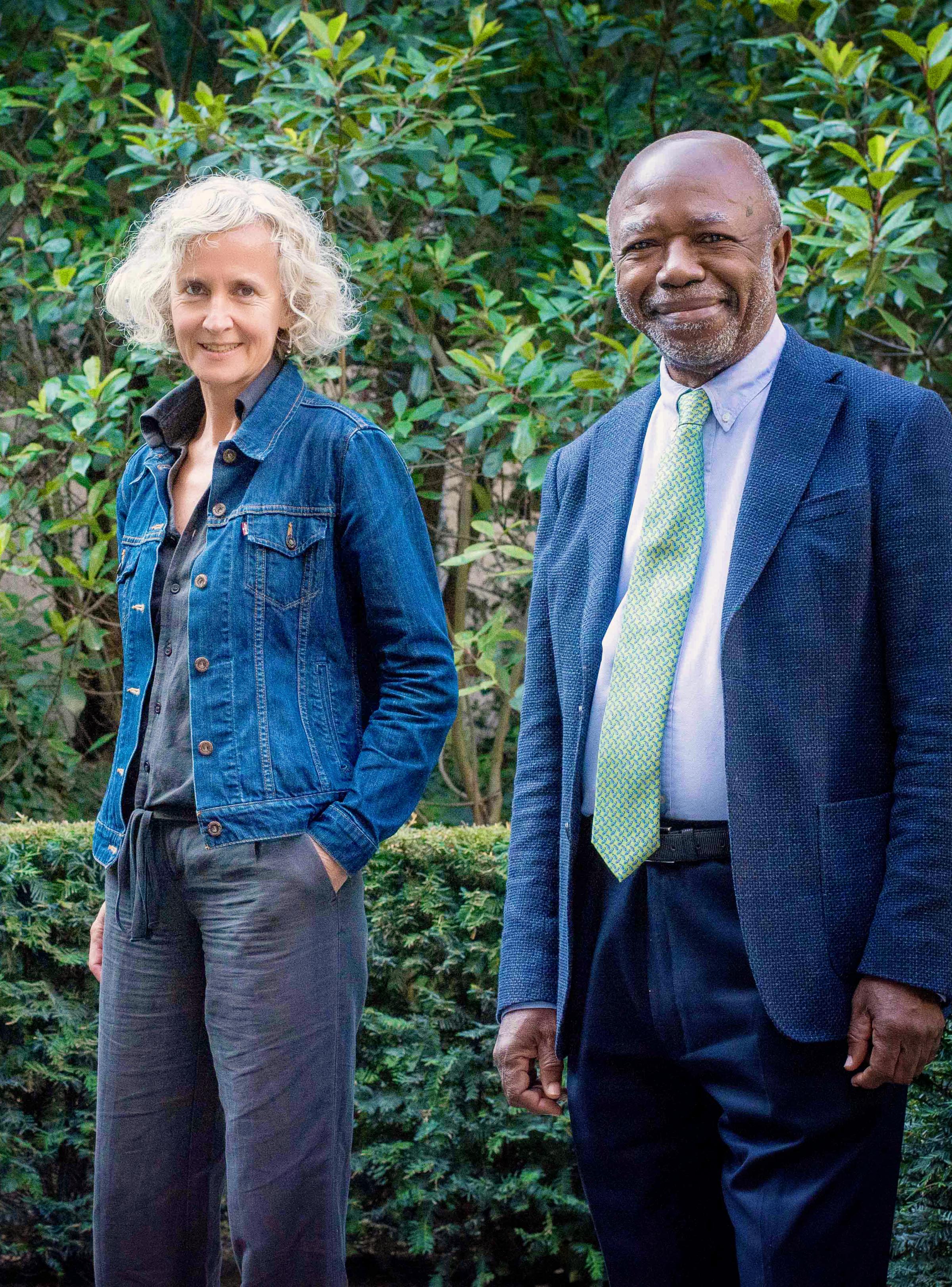

Professor Elikia M’Bokolo has been leading the studies carried out by UNESCO on the educational use of general textbooks on African history. This Congolese historian is the initiator of the “Bokundoli” programme, which focuses on the DR Congo, a collaboration with key partners including the Congolese organisation IIP (Investing In People) and the Belgian NGO CEC (Coopération Éducation Culture). The pilot programme that has been set up is intended to allow the Congolese education system to renew the way it teaches young Congolese people about citizenship and a historical awareness of their country. It has received financial support from the DGD (Belgian Development Cooperation agency), WBI (Wallonia-Brussels International) and the King Baudouin Foundation. Interview.

Your role involves revisiting the history of Congo to allow young Congolese to appropriate their own history, aside from the history written by the colonial powers, including the Belgians as major actors. Has this history been glossed over by European historians?

That was not their explicit intention. Colonisation, however, was based on beliefs that were not built on the realities experienced by the people who suffered it. As a result it has been viewed as one of the most significant chapters in the history of Congo. The Congolese, however, were not actors in this process, but rather victims of it. Between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 18th, unlike the situation in West Africa, the first attempt at colonisation in Congo failed. Political élites in the Kingdom of Congo had initially seemed to favour openness to Europeans, but the slave trade destroyed all this: they decided to close their doors to the Europeans.

Once they had been deported into slavery in America, these Congolese citizens became resistant to colonisation. In Brazil, the most important resistance movement was led by slaves deported from Congo. In Cuba and the Caribbean, slaves deported from Congo were involved in rebellions. For Europeans, going into Congo became a synonym for violence. There was no other way to take control of the country and exploit it. The first 25 years of colonisation in Congo were in fact the most violent period in the colonial history of the African continent, from 1880 until the end of Leopold's regime. The colonists established a regime based on fear and hatred of the Whites.

“Throw all the Whites in the river”

Rebellions always involved extreme violence in Congo, both on the part of the indigenous peoples and by the governing forces. During the 1920s, journalists reported statements by Congolese who told them: “Given the slightest opportunity, we will throw all the Whites in the river”. It is important, however, not to view colonisation - which spanned less than a century - as the essential or foundational time for Congo. The country had independent societies, which neither colonisation nor the subsequent regimes have ever successfully subdued. This kind of disobedience or radical refusal to surrender is one of the key characteristics of rural societies in Congo.

Is that one of the messages you want to get across to young Congolese?

Yes. We tell them: “We were not just objects in the hands of the colonists”. Learning their true history can contribute towards emancipating them and helping them to understand that their ancestors were actors in this process. They will also see that being a citizen of an independent country means not just enjoying freedom, but building a way for people to live together.

The courses that are given today are laden with ambiguity: people have appropriated the colonial narrative and are simply repeating it. There is a need to reverse that narrative and tell young people that from a very early period in the 1480s Congo was involved in globalisation, not only as a victim but as an actor.

Congo has had democratic elections, but since the Mobutu era, power has often corrupted these leaders...

Those who come to power view themselves as above the law and above society. They have adopted the same attitude as colonial governments, namely: “We are here to fill our own pockets and bellies. As for you, ordinary people, just manage the best you can.”

“Has God cursed us?”

Faced with this attitude, citizens feel powerless. We have a proverb here: “If the water is poisoned, everything you throw in it will be poisoned too.” People who go into politics and find that 90% of the people around them are embezzling public funds, realise that it would be stupid not to do the same. What we are trying to demonstrate is that the condition in which we find ourselves is not natural. In the DRC, these questions often come up: “Has God cursed us?”

Our history shows that many of our societies have been organised. Congolese people have demonstrated their knowledge and skills. Our system of passing on knowledge allowed our societies to survive despite the slave trade.

This way of teaching history is also intended to help our young people to be better human beings and live better lives, based on the human and civic values that we have in our societies. Teaching history is not just about remembering dates. It means understanding why a society has gone from one state to another and ensuring that prosperity becomes something permanent. It also means developing a critical way of thinking. I hope this is the beginning of a process of positive change in our society.

Dominique Gillerot, Managing Director of the CEC sets out the educational approach of the pilot project: “It includes a digital application. The CEC and IPP are working with Congolese teachers, who are very interested and are keen to have a training course. The application incorporates illustrations, radio and audiovisual clips and geographical maps. There has also been some significant work alongside a number of Congolese artists who draw inspiration from their country's history.”

Other stories

Inspiring engagement!

The FXBVillage model helps the poorest in the world to regain their dignity, with sustained results

Europe

"Our approach simultaneously addresses five aspects in an integrated way: nutrition, health, education, healthy housing and environment, and economic empowerment."

Other calls

Nike Community Impact Fund The Netherlands 2025

Financial support for non-profits and community organizations in Amsterdam, Amersfoort, Hilversum, and Utrecht to promote youth sports and build active, inclusive communities.

Selection announced

Nike Community Impact Fund 2023 Paris

For stronger communities in Paris, thanks to the power of sport.

Selection announced

Nike Community Impact Fund 2023 Berlin

For stronger communities in Berlin, thanks to the power of sport.

Selection announcedOther publications

Other philantrophy

Fonds Jean et Hélène Peters (Fund)

The Jean & Hélène Peters Fund supports projects in Europe that fight poverty and exclusion by meeting the urgent needs of people in difficulty.

Lomake (Fund)

The Fund will support fundamental research by world-renowned research centres and universities on new energy storage solutions, including battery development and testing.

Transdisciplinary arts research (Fund)

To support research into the relationship of the arts to other disciplines.